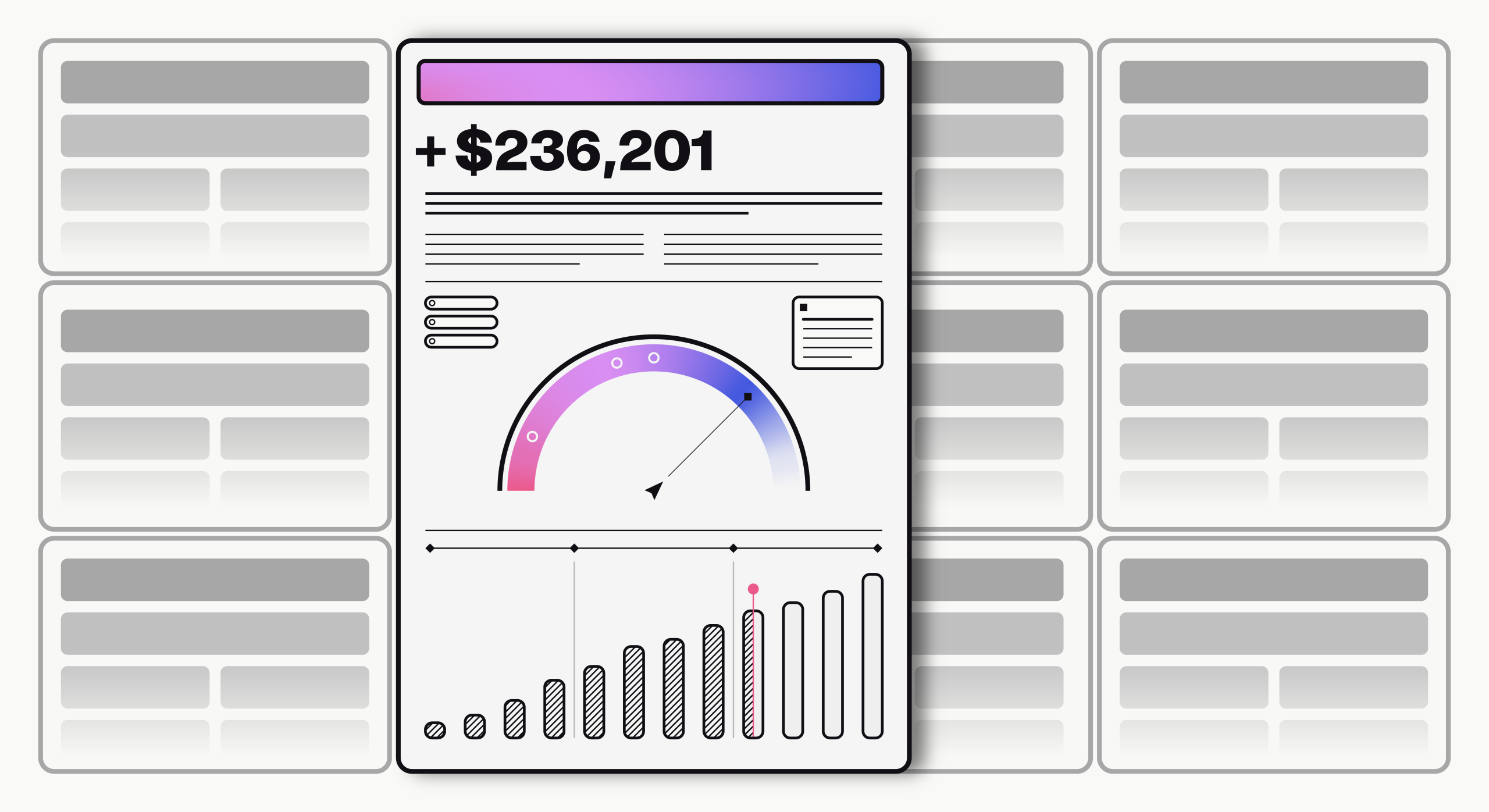

For sellers to understand a buyer's strategic priorities, they must also understand the company's financial health.

The problem? Strong financial acumen isn’t often taught on the job. And when sellers lack the knowledge to align to key metrics, they get stuck chasing low-level problems that lead to small deals—if they can even get buyers to connect.